Robots May Steal Our Jobs, but Not as Quickly as We Thought

Share

Fear of job loss to automation is growing, with each announcement of exciting technological progress generating a backlash from those who could end up unemployed because of it. Amazon Go is eliminating the need for cashiers. Self-driving vehicles won’t need truckers and cabbies at their wheels. Artificial intelligence is beginning to diagnose disease, perform surgery, and even write films and articles.

No job is safe forever, and we’re constantly being reminded of it, with little to no reassurance about what we’ll all do when computers and robots are running the world.

A report released last week by the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) offers some reprieve, bringing three pieces of welcome news:

- Widespread automation is inevitable, but it won’t happen as quickly as has been predicted.

- Automation won’t eliminate the need for human workers, rather it will transform our day-to-day tasks, likely for the better.

- Aging populations in many developed countries will lead to a decline in the total work force, leaving a gap that automation can fill, thereby contributing to overall economic growth.

Measured by tasks, not jobs

The report is the result of two years of research on automation technologies and their possible effects on the economy. Instead of focusing on sectors of the economy or whole jobs, researchers broke down 800 different occupations into the tasks and activities they’re made up of, then analyzed the automation potential of each activity.

A teacher’s job, for example, requires creating lesson plans, conveying information to students, answering questions, and grading assignments. It may be easy for a computer to take over conveying information, but harder to automate the subjective and interactive aspects of learning.

Under currently-available technology, MGI estimates 49 percent of activities can be automated, but less than five percent of jobs can be fully automated.

The activities most susceptible to automation are collection and processing of data and operating machinery in a predictable environment. These activities are most common in manufacturing, accommodation and food service, and retail trade.

Least susceptible are activities like expertise-based decision making, creative tasks, and managing people.

Globally, the report calculated automation potential equates to 1.1 billion workers, with employees in China, India, Japan, and the US making up more than half that total, and China and India together accounting for more than 700 million automatable full-time employee equivalents.

Pace setters

The pace of automation, MGI predicts, will be affected by five factors.

1) Technical feasibility: For jobs to become automated on a large scale, technology needs to be further developed and perfected to match the more complex human capabilities, like natural language understanding and emotional and social reasoning.

2) Cost: It’s only rational to automate a task if automation is cheaper than paying a human. Hardware is expensive to deploy, so automation that requires hardware has high up-front costs compared to wages. Software tends to be lower-cost, making it easier to adopt. Falling hardware and software costs will mean greater competition with human labor.

3) Labor market dynamics: Supply and demand of human labor across industries, as well as the quality of that labor, will affect how fast automation happens in different jobs. For example, countries with high manufacturing wages will automate manufacturing jobs faster than developing countries with lower wages.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

4) Economic benefits: On top of savings in wages, benefits like improved safety of workers or better quality of products will affect automation. For example, the mining company Rio Tinto deployed automated haul trucks and drilling machines and saw more than a 10 percent utilization gain as a result.

5) Regulatory and social acceptance: Even if the technology to replace jobs is available, it’s much more complex to change organizational processes, reconfigure supply chains, and adjust policies and regulations. Ethical doubts and public perception around machines replacing humans in intimate settings like hospitals, or making life and death decisions in scenarios like driving, also impact automation rate.

Shift happens

No one wants to lose his job to a computer, but MGI’s report makes the important point that as populations age, we will actually need automation-powered growth. Today, 15 percent of the US population is over 65, but by 2060 over-65s are predicted to grow to 24 percent of the population. That means fewer workers in an economy that will need to keep growing, and automation could be part of the solution.

This isn’t the first time in history that technology has replaced jobs, or the first time people are resistant to it. This time may feel more significant because artificial intelligence and machine learning are making it possible for computers to do tasks we never thought they’d be able to do.

But before the Industrial Revolution, it also seemed unthinkable for steam to power factories or for machines to cut and shape metal tools. And guess what? The Industrial Revolution led to the standard of living steadily improving for the entire populations of affected countries.

As the report’s executive summary points out, when farm employment started to drop in the early 1900s and manufacturing employment fell after 1950,

“...new activities and jobs were created that offset those that disappeared, although it was not possible to predict what those new activities and jobs would be while these shifts were occurring.”

40 years ago, we wouldn’t have been able to predict that in 2017 we’d have millions of people employed as programmers, web designers, and software engineers—yet here we are.

Technological advancement isn't likely to slow down, leaving us no choice but to adapt. But if McKinsey's predictions are accurate, we'll have more time to make that transition than we thought.

Image Credit: Shutterstock

Vanessa has been writing about science and technology for eight years and was senior editor at SingularityHub. She's interested in biotechnology and genetic engineering, the nitty-gritty of the renewable energy transition, the roles technology and science play in geopolitics and international development, and countless other topics.

Related Articles

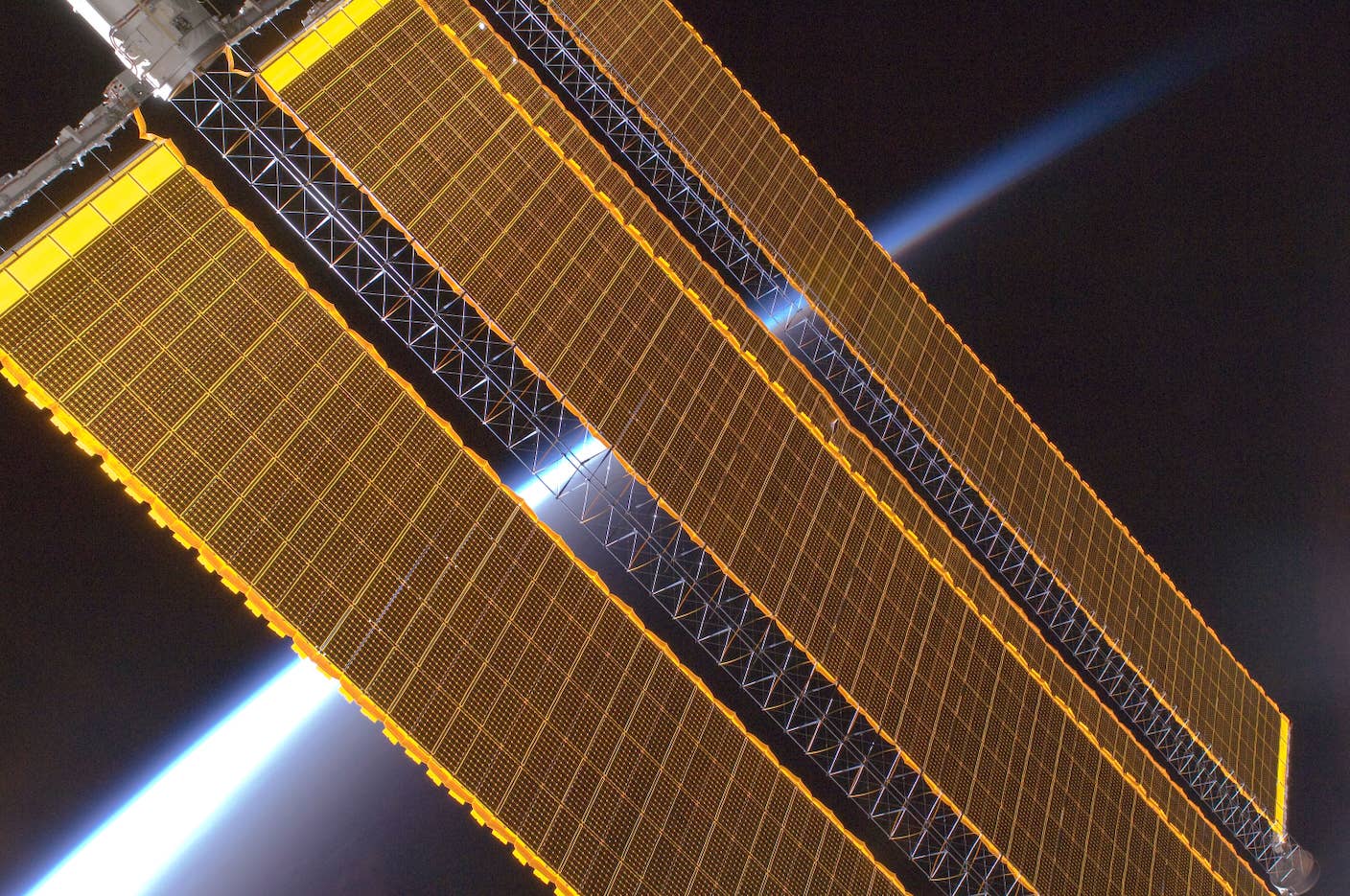

Data Centers in Space: Will 2027 Really Be the Year AI Goes to Orbit?

These Robots Are the Size of Single Cells and Cost Just a Penny Apiece

Hugging Face Says AI Models With Reasoning Use 30x More Energy on Average

What we’re reading