Scientists Hacked a Cell’s DNA and Made a Biocomputer Out of It

Share

Our brains are often compared to computers, but in truth, the billions of cells in our bodies may be a better analogy. The squishy sacks of goop may seem a far cry from rigid chips and bundled wires, but cells are experts at taking inputs, running them through a complicated series of logic gates and producing the desired programmed output.

Take beta cells in the pancreas, which manufacture and store insulin. If they detect a large spike in blood sugar, then they release insulin; else they don’t. Each cell adheres to commands like these, allowing us—the organism—to operate normally.

This circuit-like nature of cellular operations is not just a handy metaphor. About 50 years ago, scientists began wondering: what if we could hijack the machinery behind these algorithms and reprogram the cells to do whatever we want?

Now, a team of scientists led by Dr. Wilson Wong at Boston University directly hacked a human cell’s operating guide—its genetic code—and enhanced it with synthetic biocircuits that allowed it to obey over 100 sets of different logical operations, effectively uprooting nature as the sole programmer of life.

Although these cells don’t have any immediate use, the tools developed will likely benefit other bioengineers eager to tinker with evolution. And the promises of synthetic biology are great.

“These re-engineered organisms will change our lives over the coming years, leading to cheaper drugs, 'green' means to fuel our cars and targeted therapies for attacking 'superbugs' and diseases, such as cancer,” wrote Drs. Ahmad Khalil and James Collins at Boston University, who were not involved in the study.

Hacking life

The work, published in the prestigious journal Nature Biotechnology, builds on decades of previous research that aims to turn our cells into tiny, powerful microcomputers.

“A lot of synthetic biology is motivated by this idea that…you only understand something if you can build it,” says Dr. Joel Bader, a computational biologist at Johns Hopkins University who was not involved in the study.

Because of their relatively simple circuitry, most work has focused on bacteria and baker’s yeast. A few years ago, scientists tinkered with the yeast’s metabolic pathways and engineered it to produce a molecule used to make anti-malaria drugs from sugar. Other teams have made bacteria that convert carbon dioxide into liquid fuels, essentially paving the way for artificial photosynthesis. Scientists have even managed to link together two synthetic gene circuits, allowing teams of bacteria to carry out simple computations.

But extending these successes to mammalian cells has been extremely challenging. At its core, synthetic biology uses molecular tools that snip, fuse, block or otherwise manipulate an organism’s DNA. Unfortunately, the ones used to tinker with a bacteria or yeast’s genome is useless in mammalian cells.

What’s more, targeting one gene isn’t enough. To program new genetic biocircuits, scientists often need to regulate the activity of a dozen genes: amping some up while shutting others down. For things to operate as planned, each component of the system has to work effectively and in sync.

Scientists have traditionally tried to do this with a family of proteins called transcription factors, which bind to DNA and regulate its expression—that is, whether or not it gets recoded into proteins. But all of these factors behave a bit differently, making it tough to use multiple factors at once.

Because of this, “circuits with multiple inputs and multiple outputs remain scarce,” explains Wong.

Biological Boolean

To get around these problems, Wong’s team turned to a powerful molecular multi-tool: DNA recombinases, which bind to specific sequences on a DNA strand, make a cut and stitch up any open ends (“recombine” DNA pieces).

It’s like editing a video on film: to delete or add scenes, the filmmaker needs to precisely cut the physical film, toss or insert additional bits and tape everything back together.

In this way, scientists can control whether or not a protein is produced: when the DNA recombinase becomes active, it chops away a gene—and voila, no protein; otherwise, the cell makes the protein as usual. It’s the biological equivalent of a binary system, performing the simplest of logical operations—a NOT gate (if something happens, don’t do something).

If you’ve ever played around with an Arduino, you’d probably agree the simplest way to build a circuit is to have a light bulb as output. Synthetic biology, for all its complexity, is the same.

The “light bulb” that the team used is actually a gene snippet that encodes a protein that glows green under UV light, called green fluorescent protein, or GFP. Normally a cell would happily make the protein and itself glow. To build their NOT gate, the team added another gene instruction before the GFP gene—a termination sequence, which is the genetic version of “stop right there!”

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

To make their circuit more complex, the team added an if-then command. Here’s how it worked: they made a DNA recombinase that can snip away the termination sequence, but only when it’s in the presence of a drug.

When the cell doesn’t sense the drug, the DNA recombinase is inactive, the termination sequence stays in place and the cell remains translucent and colorless. If a drug is added, then the recombinase jumps into action and cuts away the NOT gate. Output? The cellular “light bulb” comes on.

While a glowing cell may seem trivial, scientists can engineer cells to light up when it detects biomarkers for cancer, HIV or other diseases. As Wong explains, you can mix a patient’s blood sample with engineered cells and instantly get your readout—a much cheaper and faster alternative to current diagnostics that require expensive machines.

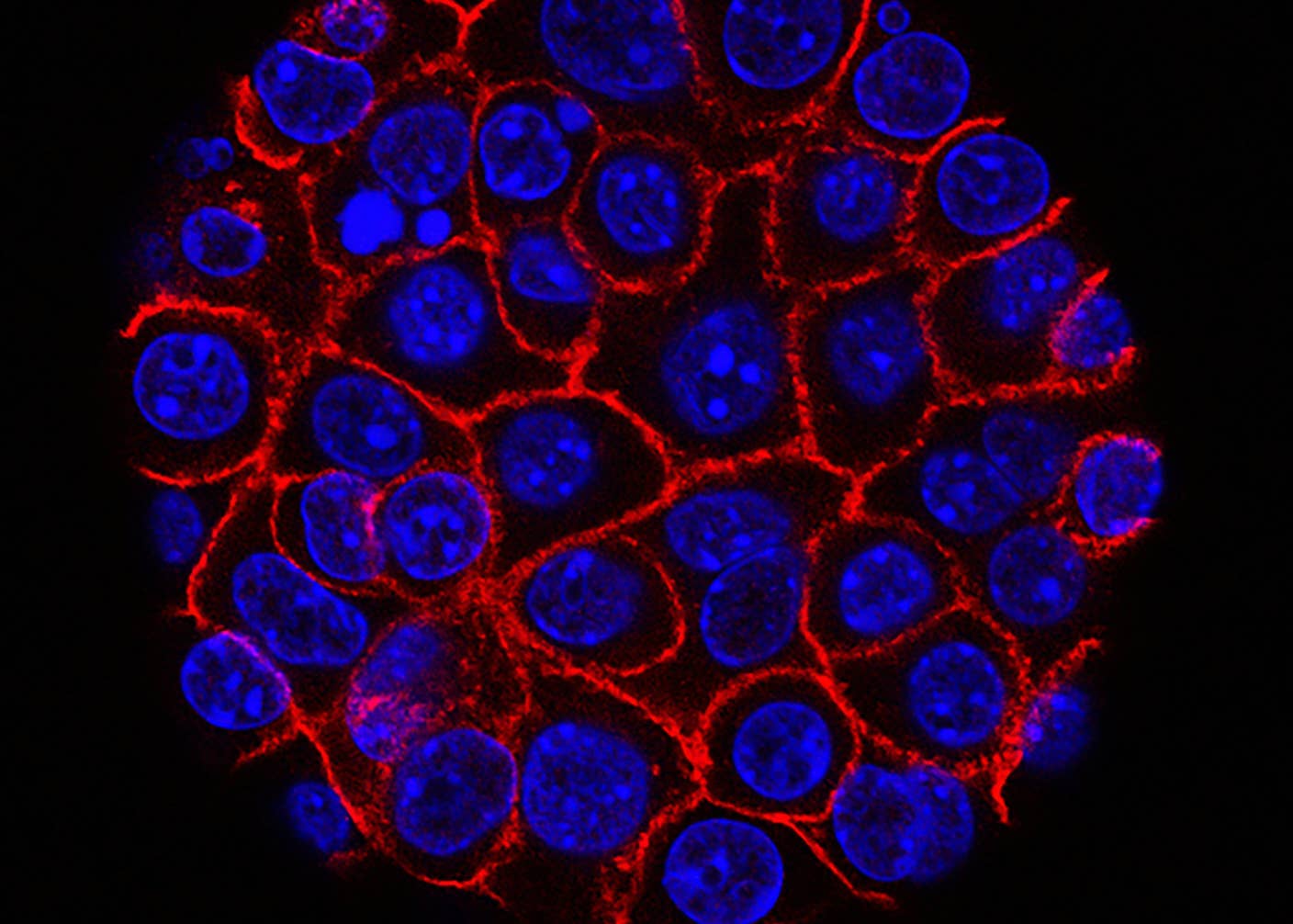

Not content with simple circuits, the team went on to construct 113 circuits in human kidney and immune cells. A staggering 96.5 percent of them worked as intended without needing further optimization, which is quite impressive because biological tools can be extremely finicky.

“In my personal experience building genetic circuits, you’d be lucky if they worked 25 percent of the time,” says Wong.

BLADE in action

The team dubbed the new tool with a catchy name, BLADE, which stands for “Boolean logic and arithmetic through DNA excision.”

But BLADE isn’t just a novelty tool only good at Boolean logic. What it offers is a way to design large-scale biological circuits, so that scientists can reliably control the actions of a cell.

Wong is already at work finding a project for his new tool, and he has his eyes on regenerative medicine. Although stem cells have the ability to turn into most (if not all) cell types, what they actually become is determined by the set of genes that push them towards a certain fate.

With BLADE, scientists could design complex if-then systems into stem cells, where one set of “if” conditions pushes the cell towards one fate (say, a neuron), while others trigger it to turn into insulin-producing beta cells.

BLADE can also give cancer therapy a boost. Scientists are already engineering immune cells that can detect cancer biomarkers and specifically target cancer cells. Programming additional biocircuits into these cells could give them even more sophistication and control: for example, AND gates would limit the immune cells to only spring into action when they detect multiple cancer markers, further lowering casualties and side effects.

Although there’s still a ways to go, scientists are hopeful. If we keep addressing the technical challenges in the field, one day we will only be limited “by the imagination of researchers and the number of societal problems and applications that synthetic biology can resolve,” says Khalil and Collins.

One thing is clear: with synthetic biology, we no longer have to play by nature’s rules.

Image Credit: Shutterstock

Dr. Shelly Xuelai Fan is a neuroscientist-turned-science-writer. She's fascinated with research about the brain, AI, longevity, biotech, and especially their intersection. As a digital nomad, she enjoys exploring new cultures, local foods, and the great outdoors.

Related Articles

These Supercharged Immune Cells Completely Eliminated Solid Tumors in Mice

Souped-Up CRISPR Gene Editor Replicates and Spreads Like a Virus

Your Genes Determine How Long You’ll Live Far More Than Previously Thought

What we’re reading