The Most Innovative Companies Thrive When People Disrupt Themselves

Share

While the popular phrase “disrupt yourself before someone else disrupts you” is often meant for organizations, Whitney Johnson believes that people should be in the practice of disrupting themselves, too. After spending nearly a decade as an institutional investor ranked equity analyst on Wall Street, Whitney co-founded the Disruption Innovation Fund with Harvard Business School’s Clayton Christensen and created proprietary frameworks and practices that help executives understand how to unlock disruption.

Recognized as one of the 50 leading business thinkers in the world (Thinkers50), Whitney is the author of Disrupt Yourself: Putting the Power of Disruptive Innovation to Work and Dare, Dream, Do: Remarkable Things Happen When You Dare to Dream.

I recently caught up with Whitney about her latest book Build an A-Team: Play to Their Strengths and Lead Them Up the Learning Curve, which explores the strategies leaders can use to build adaptive, high-performing teams and flexible organizations.

Lisa Kay Solomon: In the world of innovation, companies often talk about disruption from new technologies and competitive business models. What does it mean at the personal level?

Whitney Johnson: We all recognize that we are living in an era of extremely rapid change. New technology is certainly a huge part of that; something that is freshly innovative today can make the lifespan journey from "cutting edge" to "obsolete" in a pretty short timeframe. Businesses have to be nimble to adapt to changing market demands.

What we sometimes forget is that all this change originates in the minds of human beings. Disruption isn’t just happening to us; we are the force behind it. If individuals aren’t being creative and working disruptively, businesses and technologies aren’t going to change and disrupt either.

People are the starting point for new ideas, and we are innately wired for change. That aspect of our humanness has to be acknowledged and nurtured in the workplace. We need to be disrupting ourselves—shaking things up professionally—every few years or we, too, can become obsolete. We will be overtaken by more agile and ambitious people—disrupt or be disrupted, just like the latest technology.

LKS: In a world of accelerating change, how should leaders be thinking about talent development, both for themselves and for their teams?

WJ: Surveys and studies abound that convince me that even more than keeping an eye on profit/loss statements and quarterly reports, leaders need to be concerned about employee engagement. High engagement drives productivity and profitability in turn; disengagement leads to decline. People, not businesses, are the basic unit of innovation and disruption; human brains are the instruments of creation. They like to be learning, thinking, engaging in problem-solving and challenge. Without a strategy for talent development, including our own, it is a matter of chance whether we will be creative enough to compete.

Leaders need to foster work environments that provide learning opportunities and new challenging roles internally. There’s a tendency to want to keep productive employees in place, but in most cases people will get bored. Most don’t stay happy doing the same things again and again, no matter how capable they are.

Valuable employees leak away to other companies when they no longer find satisfaction and growth in the work they do. Train and have open conversations about next career steps for all talented employees. Reward leaders who focus on talent development and act on the reality that sacrifice of short-term comfort leads to long-term gain.

LKS: We typically think about “S-curves” for technology. How does that concept apply to individual and team development?

WJ: The S-curve is a model that was originally devised to help provide predictability to an unpredictable process—how rapidly a new idea or innovation will penetrate and then permeate a market or culture. People are also unpredictable, and it’s impossible to describe or predict the process of human change with any kind of scientific formula. But the S-curve can help us model this process. We talk about learning curves for people; the S-curve is a visualization of a learning curve.

At the low end of the S-curve we think "entry level." There’s a lot to learn, and a relatively high level of discomfort while we get a handle on the new job. In time, we gain competency and shift into a higher gear that propels us up the steep back of the curve.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Eventually we’ve mastered pretty much everything associated with the job, and the curve flattens out. Learning has diminished and so has challenge. We’re coasting across a plateau, in danger of boredom, complacency, and stagnation. If there isn’t an opportunity for employees at this stage to jump to a new curve, starting again at the low end of high learning, they will usually leave, or you will wish they would.

Everyone is on a curve. The key to building an A-Team is to balance the curves occupied by members of any given team and give attention to developing each individual on their particular curve, while planning for what will come next.

LKS: You advocate that leaders hire for high potential rather than maximum qualifications. Can you share more about this idea?

WJ: This seems counterintuitive and is certainly counter to the way most leaders are hiring. In fact, it’s more common to inflate the qualification required for a position and then hire the candidate who most closely fills those exaggerated requirements. But it’s a mistake that contributes to the revolving door of employees leaving for other opportunities almost as soon as they’ve been hired and trained.

Every S-curve has a shelf life. When we hire the most qualified candidate in the pool of applicants we are often shortening that shelf life. We should be hiring high-potential people who nevertheless have plenty to learn in the role we’re hiring them for. They will be more engaged and productive for a longer period of time. The highly qualified candidate will more quickly exhaust the potential of the learning curve and be looking around for something else to do.

Optimally, employees will ride a learning curve for three or four years. But a large percentage of the workforce is looking for a new job within a half year. It’s a costly waste of the investment we make in recruiting, hiring, and training. Human resources are resources like the others we invest in. They should be developed, not come ready-made.

Image Credit: popovartem / Shutterstock.com

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

Lisa Kay Solomon is a well-known thought leader in design innovation with a focus on helping leaders learn how to be more creative, flexible and resilient in the face of constant change. Lisa is the Chair of Transformational Practices and Leadership at Singularity University a global community of smart, passionate, action-oriented leaders who want to use exponential technologies to positively impact the world. She coauthored the Wall Street Journal bestseller, Moments of Impact: How to Design Strategic Conversations that Accelerate Change, and more recently, Design a Better Business: New Tools, Skills and Mindset for Strategy and Innovation. Lisa is a frequent keynote speaker on innovation, design thinking and leadership at global conferences and business schools. A passionate educator, Lisa has taught at the revolutionary Design MBA program at California College of the Arts and has developed and led popular classes for Stanford d. School such as Networking By Design and Design With the Brain in Mind. She is also the Executive Producer of the annual Inspired4Schools conference, a design leadership program for educators, and is on the leadership committee for The Nueva School’s Innovative Learning Conference, a biennial gathering for trends related to the future of education.

Related Articles

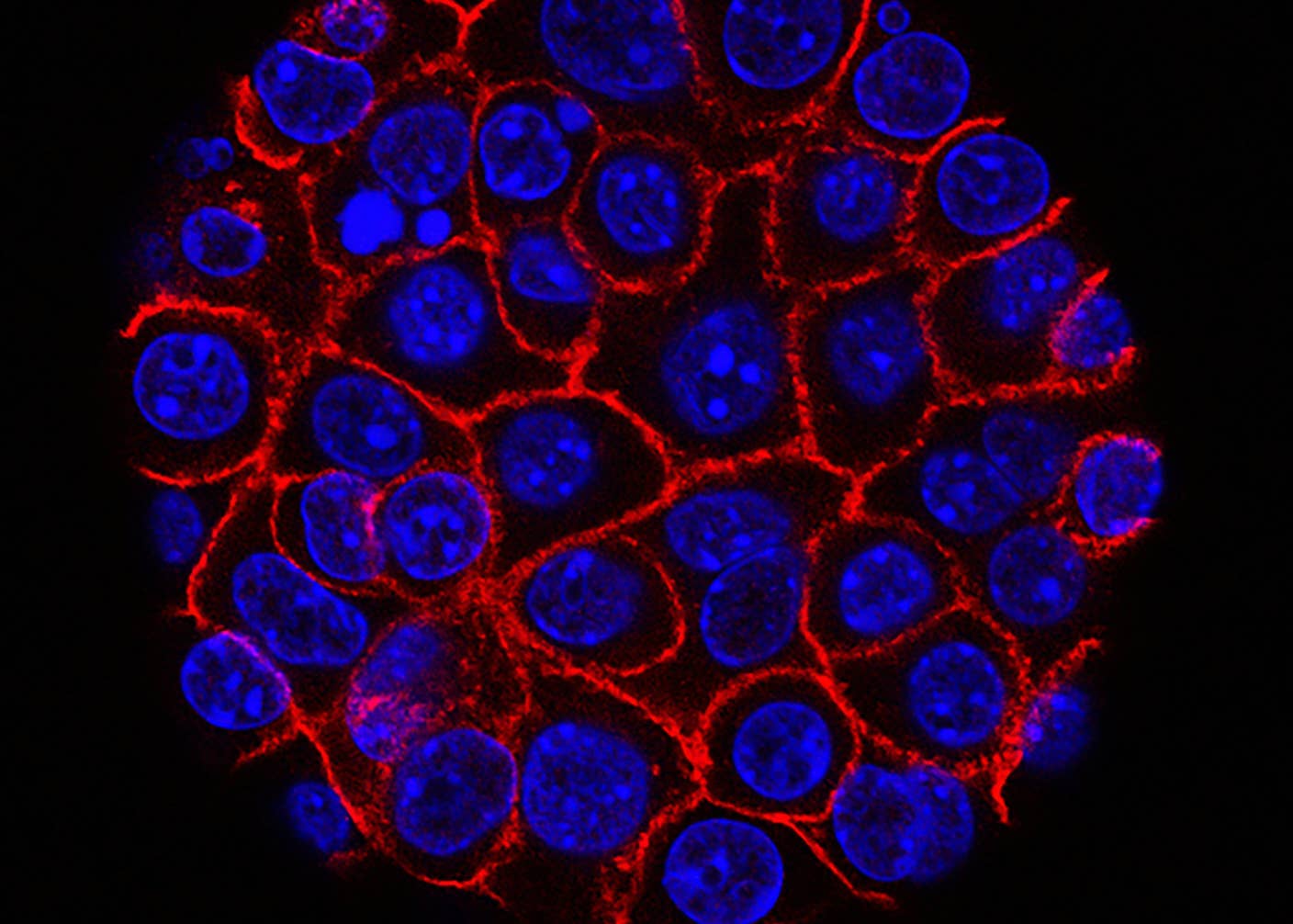

These Supercharged Immune Cells Completely Eliminated Solid Tumors in Mice

New Device Detects Brain Waves in Mini Brains Mimicking Early Human Development

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through February 28)

What we’re reading