Would a Universal Genetic Database Be a Crime-Solving Wonder, Or an Orwellian Nightmare?

Share

The privacy of our DNA is being increasingly eroded, a phenomenon highlighted by the rash of criminal cases recently solved using publicly-accessible genomic data. Now researchers have suggested, counter-intuitively, that surrendering our genetic information to a universal forensic database could actually make unwanted intrusion less likely.

The idea of the government having access to every citizen’s DNA might sound like an Orwellian nightmare, but recent events suggest we’re not far from this being the ground truth. In April, police charged a suspect in the Golden State Killer case after linking crime scene DNA samples to a distant relative via the public GEDmatch database. Since then, similar methods have been used to close 13 cold cases.

The issue is that even if a criminal never submits their DNA to a database, if anyone remotely close to them in their family tree does, it can dramatically narrow the scope of an investigation. At the same time, law enforcement agencies are rapidly amassing databases of genetic fingerprints from convicted criminals or even simply those who have been arrested, regardless of whether they’re ever charged with a crime.

This poses a number of problems. Firstly, databases held by law enforcement inevitably end up showing the same biases present in all facets of policing—young, male, non-white populations are significantly over-represented.

The opposite is true for consumer databases, which are predominantly populated by higher income white people. But these databases also contain considerably more information than is required for forensic identification, like ancestry, family history, and health risks, which hold the potential for serious abuse.

That’s prompted researchers from Vanderbilt University to advocate for a universal genetic forensic database in a recent paper in the journal Science. The core of their argument is that law enforcement already has piecemeal and unregulated access to our genetic profiles, so it’s probably better to formalize and proactively control that access.

The authors point out that what we’ve seen this year is probably just the tip of the iceberg. While most cases so far have seen police exploit publicly-available databases, they say that in most jurisdictions a simple subpoena with a relatively low burden of proof is all that’s required to force consumer genetic testing companies such as 23andme to check if they have a match with crime scene data.

The same could be true of medical records supposedly protected by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, and even genetic information collected for biomedical research, with the exception of studies expressly covered by government-issued Certificates of Confidentiality.

As an alternative, the authors suggest the government could instead initiate a universal genetic database that would contain only the limited genetic information—likely a small subset of genetic markers with little medical relevance—required for forensic identification.

Such a registry would remove the bias associated with current collection methods, they say, as well as preventing the exposure of sensitive genetic information not relevant to law enforcement. That could remove the current stigma of criminality associated with membership of law enforcement databases and protect relatives of criminals from unnecessary investigation.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

It could also reduce well-documented reluctance to share useful genetic information among certain groups, particularly non-white ones already under-represented in biomedical research. And limiting the scope of genetic records accessible by the government should also help head off concerns about Gattaca-esque genetic discrimination.

But while it’s not explicit, underlying the proposal is the tried and tested “nothing to hide” argument so often used to justify government surveillance: this intrusion into a previously private space will only impact those engaged in illegal activity, so if you’ve got nothing to hide, you’ve got nothing to fear.

This presumes a number of things: that the authorities will only use the data they hold for the stated purpose, what they classify as illegal behavior will remain consistent, and they are competent enough to protect our data.

Revelations of clandestine surveillance programs aimed at law-abiding citizens with ill-defined scope and purpose, a global slide towards authoritarianism and regular data breaches at some of the most technically sophisticated and well-resourced companies in the world should make it clear those assumptions are misguided.

Just because the authorities can probably already access our genetic information doesn’t mean we should make absolutely sure that they can. And just because the current system means they’re likely to ensnare certain populations more effectively doesn’t mean we should make everyone more vulnerable.

The question isn’t whether our genetic data should be easily accessible; it seems it increasingly is. The question is whether it’s really sensible for control of it to be so centralized, something the authors fail to properly address.

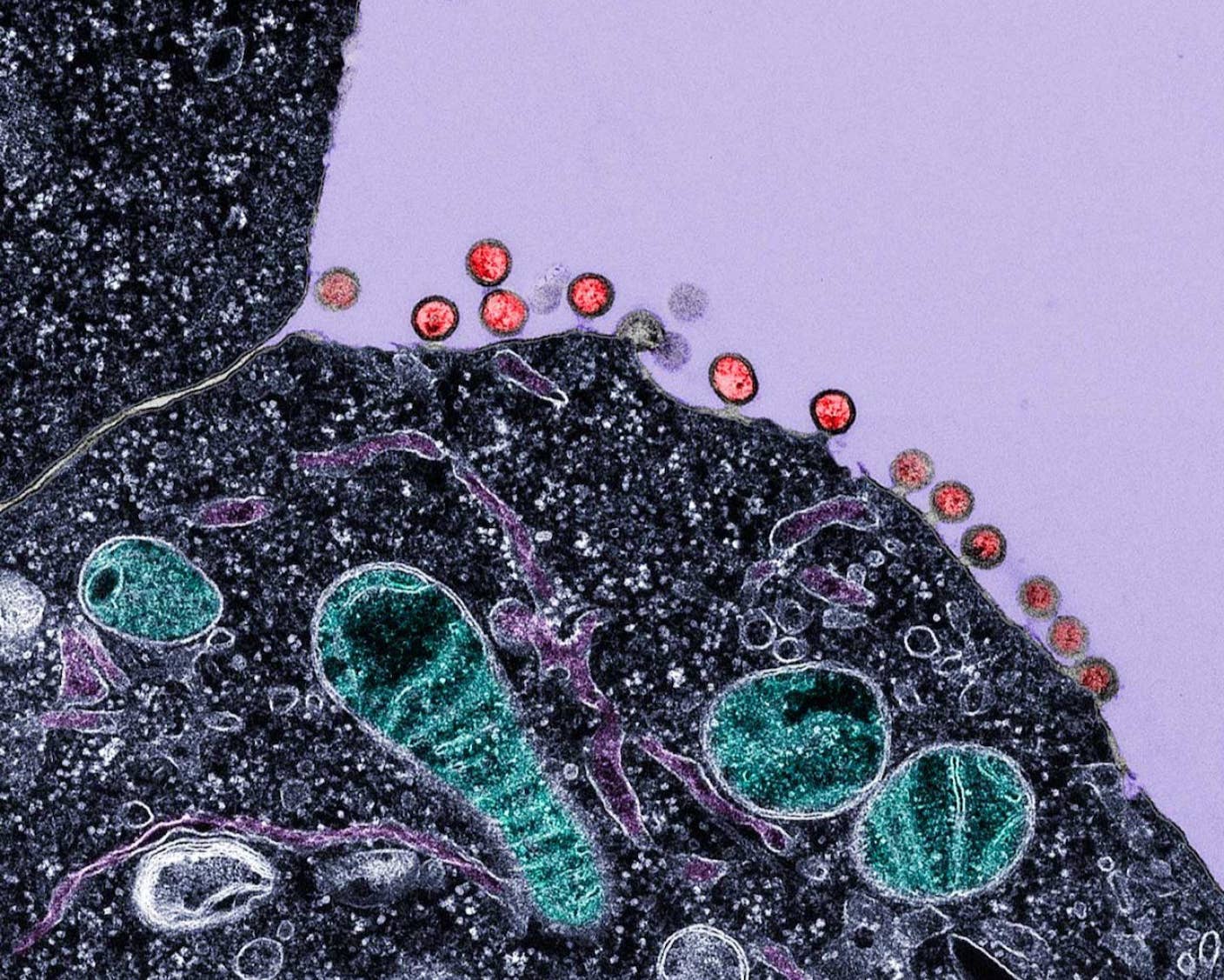

Image Credit: 300 librarians / Shutterstock.com

Related Articles

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through December 13)

New Immune Treatment May Suppress HIV—No Daily Pills Required

How Scientists Are Growing Computers From Human Brain Cells—and Why They Want to Keep Doing It

What we’re reading