New Artificial Photosynthesis Method Grows Food With No Sunshine

Share

How can we grow more food using fewer resources? Scientists have been focused on this question for decades if not centuries, as an ever-growing global population necessitates constantly seeking new ways to produce food in sustainable and affordable ways.

Here’s a question most of us have never contemplated, because it seems so unfathomable: what if crops could grow without sunlight—not vertical farm-style, where LED light replaces the sun, but in total darkness?

A paper published last week in Nature Food details a method for doing just that.

Photosynthesis uses a series of chemical reactions to convert carbon dioxide, water, and sunlight into glucose and oxygen. The light-dependent stage comes first, and relies on sunlight to transfer energy to plants, which convert it to chemical energy. The light-independent stage (also called the Calvin Cycle) follows, when this chemical energy and carbon dioxide are used to form carbohydrate molecules (like glucose).

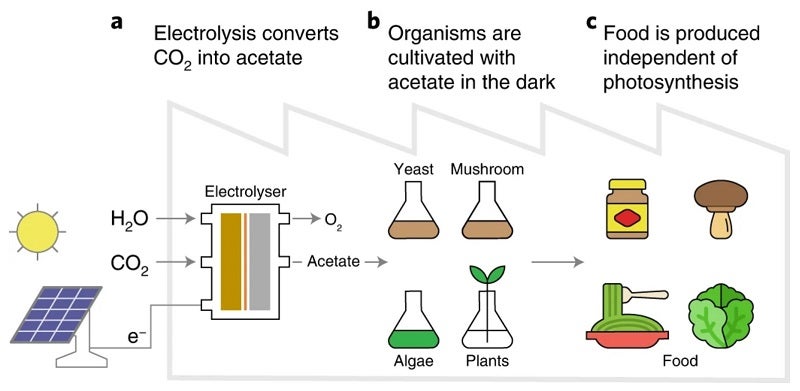

A research team from UC Riverside and the University of Delaware found a way to leapfrog over the light-dependent stage entirely, providing plants with the chemical energy they need to complete the Calvin Cycle in total darkness. They used an electrolysis to convert carbon dioxide and water into acetate, a salt or ester form of acetic acid and a common building block for biosynthesis (it’s also the main component of vinegar). The team fed the acetate to plants in the dark, finding they were able to use it as they would have used the chemical energy they’d get from sunlight.

Image Credit: Hann et al/Nature Food

They tried their method on several varieties of plants and measured the differences in growth efficiency as compared to regular photosynthesis. Green algae grew four times more efficiently, while yeast saw an 18-fold improvement.

The problem with photosynthesis, though it’s been around since the beginning of life on Earth, is that it’s only able to convert about one percent of the energy it gets from sunlight into “food” for the plant. The team also had success feeding acetate to cowpea, tomato, tobacco, rice, canola, and green pea plants.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

“Typically, these organisms are cultivated on sugars derived from plants or inputs derived from petroleum—which is a product of biological photosynthesis that took place millions of years ago,” said Elizabeth Hann, co-lead author of the study. “This technology is a more efficient method of turning solar energy into food, as compared to food production that relies on biological photosynthesis.”

Decoupling plant growth from sunlight, as bizarre as it sounds, would have huge potential benefits for food production. As climate change makes weather and thus crop yields increasingly unpredictable, it’s becoming more appealing—and necessary—to grow food in controlled environments, like those of vertical farms. Being able to grow more crops indoors would also bring produce to a whole new level of “local,” as crops that used artificial photosynthesis to replace sunlight could theoretically be grown just about anywhere.

"Using artificial photosynthesis approaches to produce food could be a paradigm shift for how we feed people,” said the study’s corresponding author, Robert Jinkerson, a UC Riverside assistant professor of chemical and environmental engineering. “By increasing the efficiency of food production, less land is needed, lessening the impact agriculture has on the environment.”

There are some key details that would need to be worked out before this methodology could be seriously considered for large-scale food production. How much energy, water, and other resources would it use relative to traditional farming or other technology-enhanced food growth techniques? Is the texture, flavor, and nutritional content of plants fed with acetate identical to those grown in sunlight?

Tinkering with nature always seems like a murky undertaking, but from the Green Revolution to the advent of modern-day GMOs, humans have been doing so for centuries; to some degree our survival has been dependent on our ability to manipulate nature. We’re seeing the fallout from that manipulation now, but techniques like artificial photosynthesis could end up being part of the toolbox we’ll need to repair the damage we’ve done—while continuing to feed a growing global population.

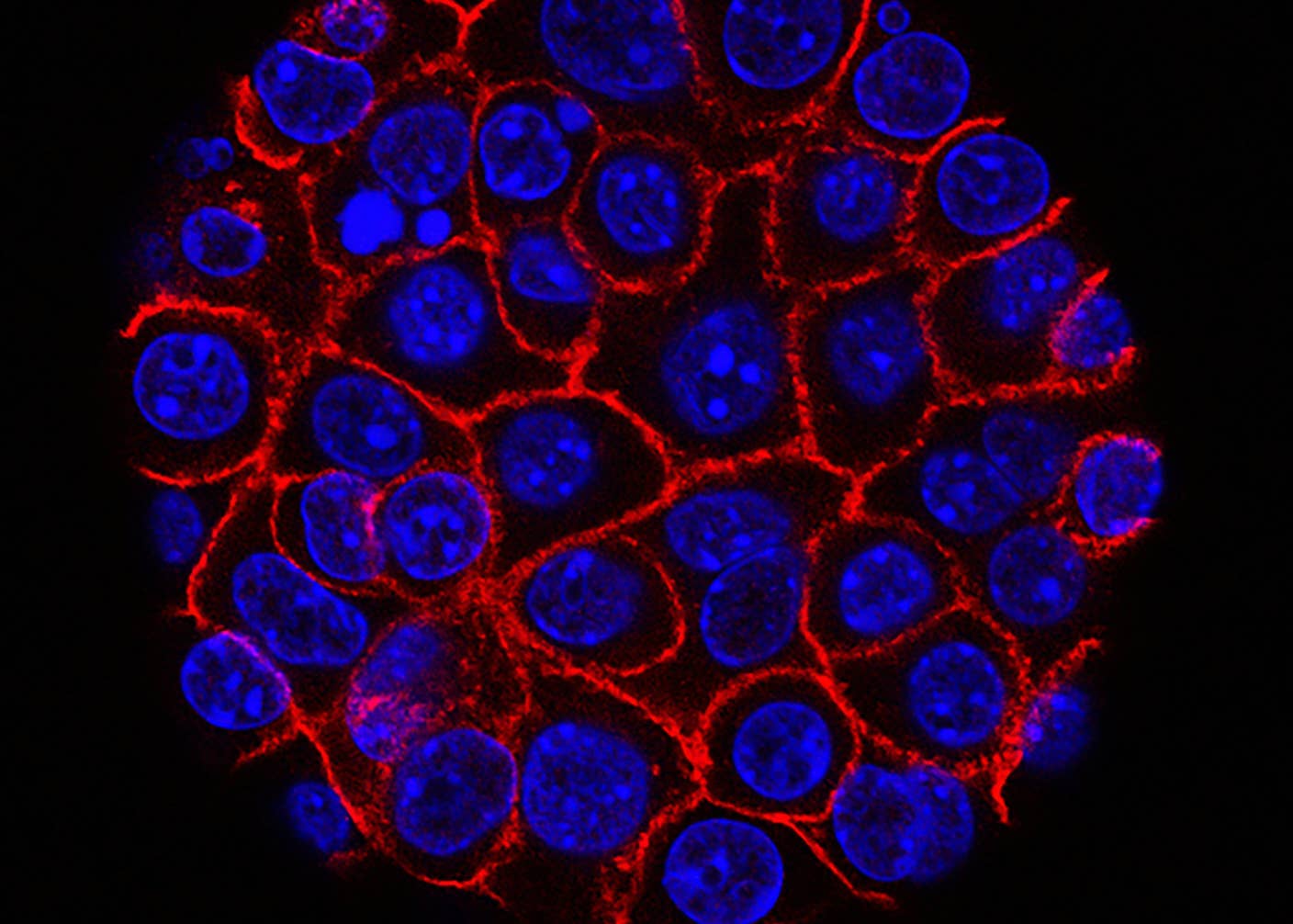

Image Credit: Marcus Harland-Dunaway/UCR

Vanessa has been writing about science and technology for eight years and was senior editor at SingularityHub. She's interested in biotechnology and genetic engineering, the nitty-gritty of the renewable energy transition, the roles technology and science play in geopolitics and international development, and countless other topics.

Related Articles

In a First, Researchers Use Stem Cells and Surgery to Treat Spina Bifida in the Womb

These Supercharged Immune Cells Completely Eliminated Solid Tumors in Mice

Souped-Up CRISPR Gene Editor Replicates and Spreads Like a Virus

What we’re reading