RoboDynamics Reveals Hard Truth About Telepresence Robots

Share

Like many of us, Fred Nikgohar remembers watching Star Wars and dreaming of the day he would have robots of his very own. Unlike most of us, however, Nikgohar grew up and founded a company to make that dream a reality. RoboDynamics has spent the better part of the last decade creating cutting edge robots, and was one of the fore-runners in telerobotics. Recently I was able to test drive TiLR, RoboDynamics' full sized telepresence robot on the market since 2008. I was also able to talk with Nikgohar about the industry. Nikgohar is one of the few people who has real experience selling human-scale telerobots. If you think your robot's technical wizardry is going to let you sell a thousand units easily, think again. There are hidden hurdles to putting robots in offices, and too many view the technology as nothing more than "Skype on wheels". RoboDynamics and Nikgohar have found some bitter (and sweet) truths about telerobotics, and what they've learned may make you rethink the concept.

Here's Fred making his pitch for the TiLR and Robodynamics:

Telerobotics is a blossoming field. Willow Garage built their own telerobot (the Texai), Anybots is bringing their QB to market, RoboDynamics has the TiLR out in the field already, and there are many smaller scale platforms out there. No matter which bot you use, the general idea seems simple: stop spending billions flying people around the world and instead have them 'teleport' into a location by operating a robot that resides there. Video and audio are piped back and forth. It sounds really cool. And I've loved all my interactions with telerobots. They are fun and exciting pieces of technology. But how many of these robots have we actually sold? For most the answer is zero. Nikgohar is the only one who's actually been trying to sell them for a few years and even he has found things to be difficult. Why?

Security. Bureaucracy. Lack of preparation. These are the hurdles that you have to clear in order to bring telerobotics into the mainstream and they are more difficult to defeat than you think. RoboDynamics wanted to put TiLRs into a major financial institution where 95% of employees were in the field, away from the home office. It was a perfect fit for telepresence. Except the red tape for bringing a camera into some banks is insane. A moving camera with streaming video? Forget about it. The robots were returned for 'legal reasons'.

What about tech industries, they're going to be robot friendly, right? RoboDynamics was working with a major (MAJOR) software company to install TiLRs. People were really excited about the possibilities. That company, however, requires every single WiFi device to have a dedicated user with a keyguard that vouches for the device at all times. Every TiLR would have required a babysitter. Why telecommute in an employee if it just means handicapping a coworker that's on site. The company's own security bureaucracy effectively killed the plan.

Businesses simply haven't updated their infrastructure to handle a population of roving real time video feeds patrolling their inner sanctums. Even the ones that want telerobots have to spend a lot of time (and money) fighting corporate lethargy to install the new test product. Some companies have adapted well and have had success with TiLR, but at least one has done so by pulling TiLR back behind the curtain so to speak. They don't want competitors to know how they implement telerobotics. Secrecy abounds in the corporate world.

Fred Nikgohar told me something that no robotics engineer had told me before: the greatest barrier keeping telerobotics from conquering the office probably isn't hardware or software, it's red tape. Maybe you wouldn't know that unless you've spent two years trying to sell a telerobot.

So should we give up on placing a telerobot in every office? No, we just need to understand what we're really selling here. Businesses can spend thousands on high quality conference rooms with life-like A/V, and anybody can video chat over Skype for free. The traditional wisdom is that telerobots let you roam around, take the conference out of the room and put it in the hallways, allowing for impromptu meetings and walking conversations. This is the "Skype on wheels" sales approach that Nikgohar thinks misses the big point of telerobotics - physical presence. There is something inescapably important about having a physical body in a place where other people have physical bodies. That's a lesson that Nikgohar and other telerobotics pioneers have learned over the years.

Since they first started to field TiLRs back in 2008, RoboDynamics has been collecting data on how people use and react to telerobots. These case studies have been remarkably insightful. Here are some interesting results:

- In an office where a telerobot is operated by a single user it takes about 4 days before coworkers start to refer to the robot by the operator's name. It's not, "where's the robot?" it's "where's Jeff?"

- About 30% of operating time is spent driving the robot around. Nearly 100% of users, however, didn't want this time to be reduced. Driving around time was great for walking conversations, thinking, etc.

- About 68% of conversations are started on the robot side. Often a coworker walks away from their own desk, seeks out the robot, and talks to the operator. This is in spite of the fact that the operator is easily accessible from the coworker's desk via email, phone, or even video conferencing.

- After a week, 61% of operators say they would be severely hampered if they had to go back to telecommuting in without TiLR.

What do these findings mean? Well, for one they indicate that there's something going on with telerobotics that is more than just "Skype on wheels". This isn't just a better teleconferencing tool, it's a way to have a presence in another space. People start to refer to the robot by your name. They seek you out by looking for your robot avatar, even if it means walking around to find it. They value the time they spend in transition with the robot - driving around, impromptu conversations, water cooler talk. When a boss sees the robot she remembers that she had to talk with Jeff about expense reports. You probably wouldn't get that with a webcam. Even with a form that looks nothing like a human, the robot starts to stand in for you. That's a key advantage that telerobotics has over every other telecommuting solution. There are social and psychological effects from having a physical body in a space.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Want an example? Let's examine the case of the $3000 work day. Nikgohar had a customer that had to travel a lot. When he was in his factory workers produced about $3000 worth of product per day. When he was out they produced $2000. Makes sense. When the boss is away you take longer breaks, you spend more time socializing. Anyone who has worked long enough has probably seen this effect. So now the customer gets a TiLR. When he is away, he starts to commute in via the robot and drive around the factory. His hope is that his virtual robotic presence will recoup some productivity. Even if its only up to $2500 or so it will be well worth it. What happens? When he's out of the office and using the robot productivity does go back up. But not to $2500, or even $3000. Suddenly the factory is producing $4000 a day. What the hell happened?

"Watch ye therefore: for ye know not when the master of the house cometh." The truth is that even when a boss is in, he's not always on patrol. Sometimes he's making phone calls, working on projects, etc. Workers know this. They get used to routines and know when they can take it easy. When the TiLR customer was out of the office, he was off his normal routine. Workers had no idea when he might jump on the robot and suddenly be in their faces, asking questions and demanding results. At least, this is Nikgohar's theory.

And it seems reasonable. Clearly, however, not everyone who wants to use a telerobot is going to face the same work situation as this particular customer. But it does highlight how important presence is. Workers don't increase productivity because there's a robot around. They work harder because the boss might arrive at any time. The robot is just the platform - it's a way to let a person teleport into a physical place. And it's that person's presence that gets results.

That's the good news about telerobotics. With case studies like this, it would seem that every boss in the country would crave a TiLR. The feedback is phenomenal. Nearly 100% of users want to keep the robot when the trial is up.

Results like these make me hopeful that telerobotics will take off despite the bureaucratic barriers that slow the adoption of the technology. There is vast potential in this field. The emerging market, as Nikgohar describes it, is an ecosphere full of many different niches that telerobotics companies can fill. Some businesses want to cut travel accounts and still foster inter-office visits. Others want increased agility in the ways their offices can be structured geographically. Many want a means to teleport a client into their offices or factories. Likewise, companies need a way to make experts more mobile - to allow a specialist to be in Asia in the morning, Europe in the afternoon, and stateside by evening.

Each of these niches could be filled by their own telerobotics company that focuses on a particular use case. For expert-teleportation, medicine is going to be a huge application. Telemedicine could revolutionize healthcare in remote parts of the world, and emerging economies may be the biggest proponents of this form of telerobotics. In telemedicine, robots won't simply be conveying audio and video, but actions as well. A doctor may use one telerobot for making rounds in one country and then log onto another robot to perform a surgery on a different continent.

Surprising to me, Nikgohar pointed to elder care as one of the most important markets for telerobotics. I should have anticipated his insight - we've often discussed how the world is getting older and requiring more attention from medical professionals. How many doctors make house calls? Telerobots could enable that on a large scale. Something like $28k worth of GDP in the US is consumed for every month an elder spends in a full time care facility. Robots could help keep grandma in her own home and save the economy at the same time.

Clearly the potential exists for their not to be just one successful telerobotics company but dozens of them. Whoever enters the field will owe a lot to RoboDynamics and their innovations, and should take to heart the lessons Nikgohar has learned. This technology can, and likely will, grow in the upcoming years, but it's going to require a lot of tender care. Those looking to sell telerobots need to get their customers fighting their own lethargy well before they ship a single bot. In the end, I hope that telerobotics really takes off. I want to see a day when my kids can teleport to India during history class, jump in a rain forest robot for biology, and explore the surface of Mars in a rover for extra credit. Most of this technology is ready now, we just need to work to make it happen.

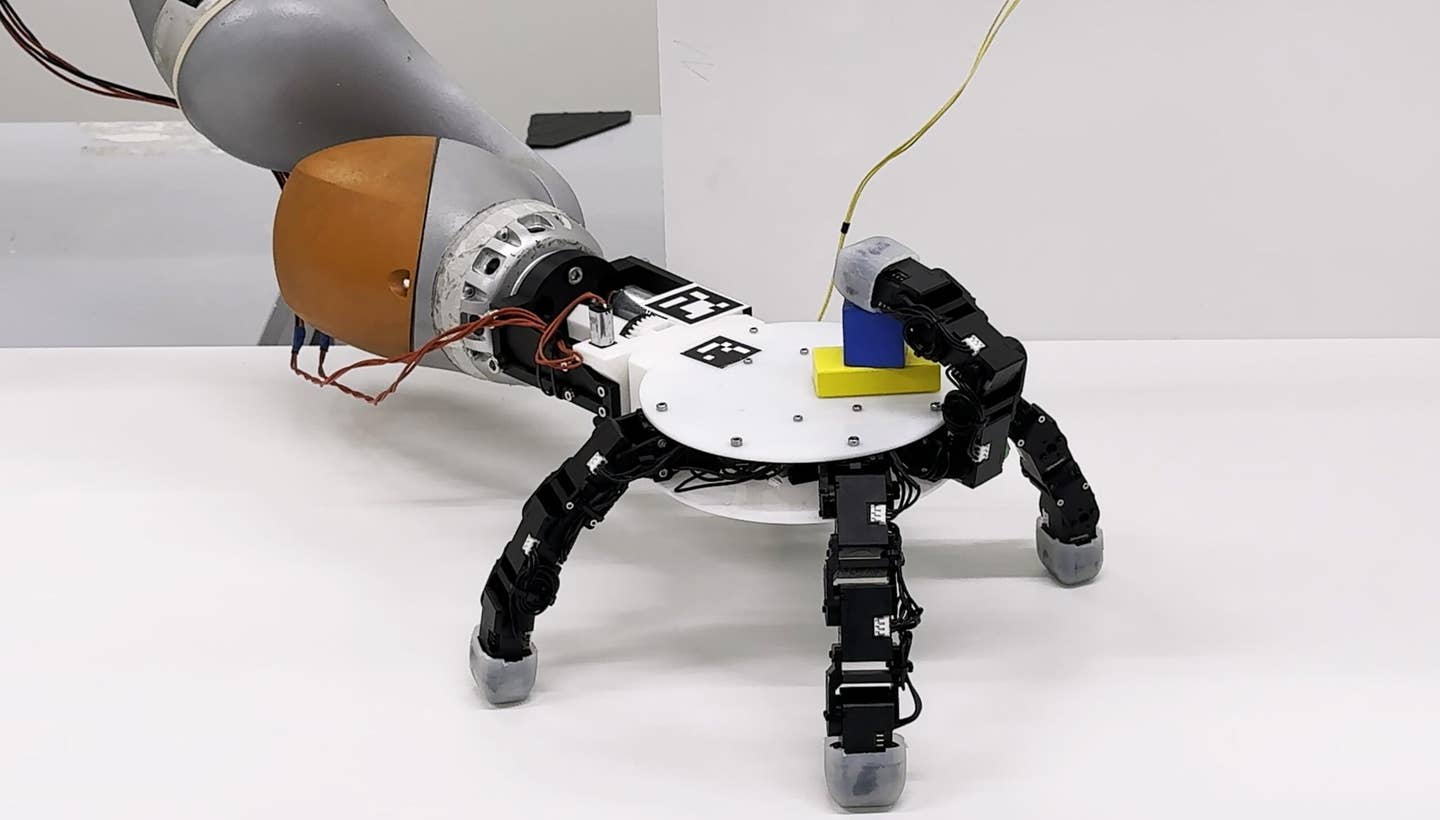

[image credits: RoboDynamics]

[video credits: RoboDynamics]

[source: Fred Nikgohar, RoboDynamics]

Related Articles

This ‘Machine Eye’ Could Give Robots Superhuman Reflexes

This Robotic Hand Detaches and Skitters About Like Thing From ‘The Addams Family’

Waymo Closes in on Uber and Lyft Prices, as More Riders Say They Trust Robotaxis

What we’re reading