Latest Tool to Fight Cancer Is a Crowdsourcing ‘Asteroids’-Like Mobile Game

Cancer Research UK is asking humans to sort through its data to mark genetic areas that have extra copies of a particular chromosome because, it says, humans can see the disparities better than computers. And they're doing it with a mobile game.

Share

The promise of genetics to shed light on how we prevent and treat disease has been inextricably linked to the growth of computer power since the first human genome was sequenced in the 1990s. Computers account for faster, cheaper sequencing, and they allow researchers to sort through huge troves of data to look for the correlations between a specific genetic mutation and a particular health problem.

But Cancer Research UK, a group that has made notable advances in the genetic understanding of breast cancers, is turning that paradigm on its head. The organization is asking humans to sort through its data to mark genetic areas with extra copies of chromosomes because, it says, humans can see the disparities better than computers.

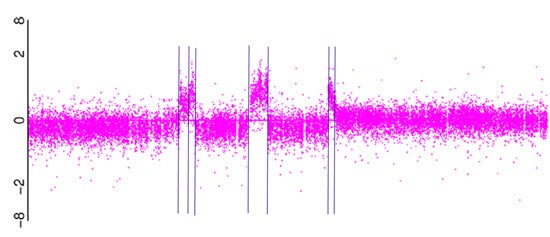

“Although the software is good, it’s nowhere near as good as the human eye for spotting subtle shifts in copy number,” the organization explained in a press release announcing its efforts to recruit citizen scientists.

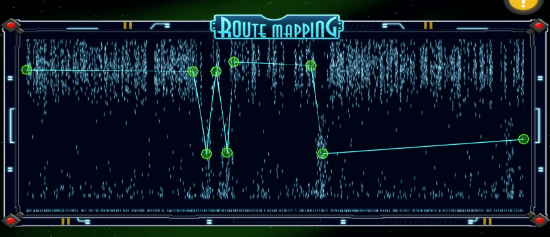

Sorting through millions of DNA microarrays doesn’t sound like much fun, you say? Cancer Research has you covered. They’ve gussied the DNA microarrays up as “Element Alpha” and invited video gamers to navigate their way through it to earn maximum points while simultaneously shooting down asteroids.

“Racking up the combined data crunching power of what we hope will be thousands of casual gamers will help our scientists spot the subtle patterns and peaks and troughs in the data, which correspond to DNA faults,” Cancer Research said in a news release.

In early tests, the gaming data has been as much as 15 percent more accurate than computers, the New York Times reported.

Here’s what the DNA charts look like:

And here’s what the spacescape filled with floating Element Alpha looks like:

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Researchers will use the crowdsourced data to focus their studies first on the peaks and valleys. They hope starting in the most pertinent places will deliver clinical treatments faster than previous genetic research has. Genetic oncologists suffer from a problem of abundance: There is enormous genetic variation among and even within tumors.

Serious gaming, or gaming with a larger social purpose, has been an area of interest and development for more than a decade. The bulk of the games serve to educate the player in some way. Re-Mission, for example, educates young cancer patients about their treatments, while also reportedly boosting their motivation to fight the disease. But at least one other serious game doubled as a way to crowdsource data-crunching: Foldit asked players to fold proteins and helped researchers fill in gaps in their understanding of how the HIV virus works.

Cancer Research UK first flirted with serious gaming in 2012 with a desktop Web crowd-sourced research project called Cell Slider.

Genes in Space emerged from a 2013 hackathon that the three Internet giants Amazon, Google and Facebook, helped put on. Ultimately made by UK game shop Guerrilla Tea, it’s available for iOS or Android.

Images: Cancer Research UK

Cameron received degrees in Comparative Literature from Princeton and Cornell universities. He has worked at Mother Jones, SFGate and IDG News Service and been published in California Lawyer and SF Weekly. He lives, predictably, in SF.

Related Articles

Autonomous AI Agents Have an Ethics Problem

Thousands of Everyday Drone Pilots Are Making a Google Street View From Above

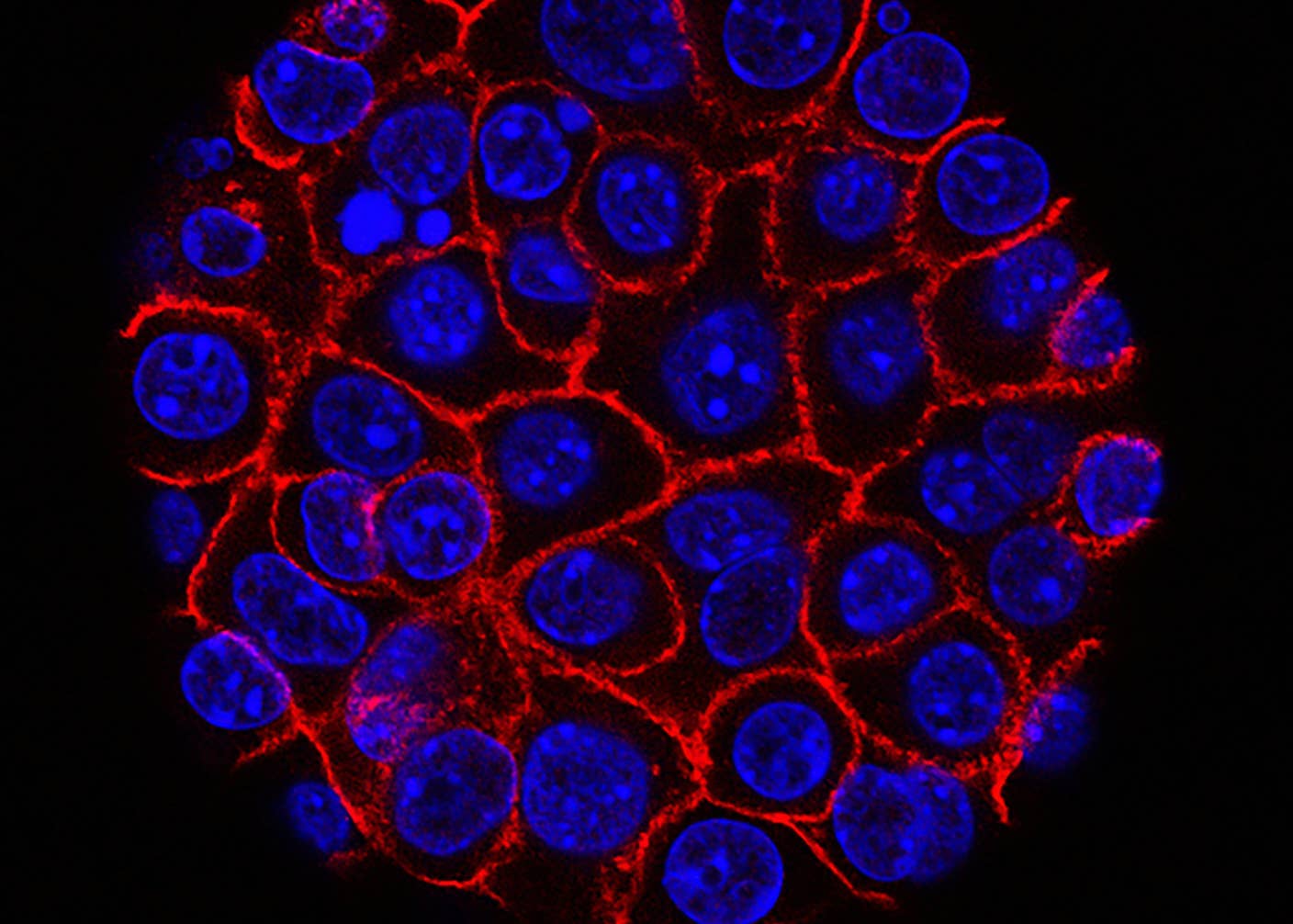

These Supercharged Immune Cells Completely Eliminated Solid Tumors in Mice

What we’re reading