Lab-Grown Retina from Stem Cells Responds to Light

Share

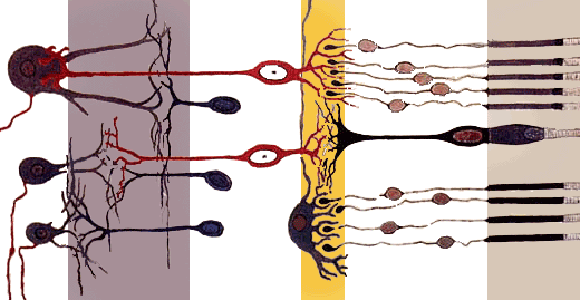

The retina is a complex and fragile piece of equipment, but without it, the world would be completely dark.

With a number of diseases that can erode the delicate tissue and little that conventional medicine can do to fix it, researchers have explored the three major cutting-edge medical approaches: computerized implants, gene therapy and stem cells.

A bionic eye is already on the market in the United States and Europe, and trials of gene therapy approaches have seen promising early results. But stem cell researchers have struggled to coax the malleable cells to form the 10 layers of the retina. And, crucially, no one had, before now, produced lab-grown retinal cells that they demonstrated would respond to light.

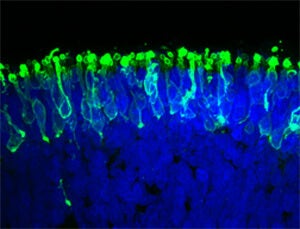

Researchers at Johns Hopkins pulled it off, they reported in a paper published recently in Nature Communications. They cultivated a three-dimensional complement of retinal tissue, including functioning photoreceptor cells that responded to light, from induced pluripotent stem cells.

“We have basically created a miniature human retina in a dish that not only has the architectural organization of the retina but also has the ability to sense light,” said Valeria Canto-Soler, the senior author and an assistant professor of ophthalmology at Johns Hopkins medical school.

The researchers placed an electrode into a photoreceptor cell and gave it a pulse of light. The cells reacted biochemically like retinal rods would in a human eye. Rods enable vision in low light, and there are far more of them than cones.

Once they become retinal progenitor cells, the stem cells were allowed to develop on their own. They specialized appropriately; there were, for example, for more rods than cones.

“When we began this work, we didn’t think stem cells would be able to build up a retina almost on their own. In our system, somehow the cells knew what to do,” Canto-Soler said.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

However, the retina was likely not producing a signal from the light stimulus that the brain could decode, Canto-Soler said. The photoreceptors are only one step in the process. The lab retina doesn’t yet comprise all of the functions of the human eye and its links to the visual cortex of the brain.

But compared to early work producing retinal cells from stem cells, which Singularity Hub reported in 2010, Canto-Soler’s team got much farther. The 2010 work boasted getting the cells to specialize at all; the latest paper boasts photoreceptors further specialized into rods and cones, and the rods, at least, work.

The ultimate goal of this work is to be able to grow replacement retinas for people suffering from macular degeneration, retinitis pigmentosa or any of the other diseases that destroy the retina. But the retina made at Johns Hopkins is like a rough draft; it’s not ready for implant. Imperfect replicas could be useful for medical research, though. Any retina produced from the stem cells of a patient with a particular disease would almost certainly show signs of the disease in vitro, where experimental treatments can be tried without the fear of side-effects.

Of course, it may take more than just growing stem cells in a dish for them to assume the precise shape of the retina: 3D printing could play a role. At the end of 2013, researchers demonstrated that eye cells, while delicate, can survive serving as ink in a 3D printer.

All told, there are so many promising approaches to treating the loss of sight that if your kid brother suddenly wants to know if you’d rather be deaf or blind, you might want to go with blind.

Photos: Johns Hopkins Medicine, Pressmaster / Shutterstock.com, public domain drawing by Santiago Ramon y Cajal

Cameron received degrees in Comparative Literature from Princeton and Cornell universities. He has worked at Mother Jones, SFGate and IDG News Service and been published in California Lawyer and SF Weekly. He lives, predictably, in SF.

Related Articles

AI Now Beats the Average Human in Tests of Creativity

Humans Could Have as Many as 33 Senses

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through January 24)

What we’re reading