CRISPR Pill May Be Key in Fight Against Antibiotic Resistance

Share

Even since Alexander Fleming stumbled across penicillin—the first antibiotic drug—scientists knew our fight with evolution was on.

Most antibiotics work by blocking biological processes that allow bacteria to thrive and multiply. With prolonged, low-dosage use, however, antibiotics become a source of pressure that forces bacteria to evolve—and because these microorganisms are extremely adept at swapping and sharing bits of their DNA, when one member becomes resistant, so does most of its population.

Even more terrifying is this: because the same family of antibiotics generally act on the same biological pathways, when bacteria generate a mutation that resists one type of drug, it often renders that entire family of drugs useless.

The arms race with increasing high rates of antibiotic resistance has forced scientists to think outside the box. Although still a work in progress, teams of scientists are now working on a truly creative strategy: a pill carrying the genome-editing power tool CRISPR that instructs harmful bacteria to shred their own genes to bits.

In essence, scientists are returning CRISPR to its roots. While best known as a handy way to manipulate DNA in mice and humans, CRISPR is actually a part of the bacteria’s immune defense system.

Just like our immune systems can turn against ourselves, scientists are now hoping to give harmful bacteria a destructive autoimmune disease.

When optimized, a CRISPR pill could have the ability to precisely target single strains of harmful bacteria, while leaving other types—including beneficial bacteria in the gut—intact.

The slow and obsolete

First, the bad news: we’re rapidly losing our war on microbugs, and if things don’t change we’re heading full throttle into an antibiotic apocalypse.

Part of the bacteria’s survival prowess comes from their ability to rapidly multiply. Under the right conditions—a damp, nutrition-packed human cell, for example—the common gut bug E. Coli multiplies exponentially, doubling every thirty minutes. This gives their DNA plenty of chances to mutate and for the species to adapt.

What’s more, bacteria aren’t stingy about sharing their DNA. Antibiotic-resistant genes are often carried on snippets of genetic material that floats around in the bacteria’s innards. Microbugs can literally extend a tube out to their neighbors to inject these genetic pieces, thus sharing their resistant genes far and wide.

In what is likely the most chilling demonstration of antibacterial resistance in action, you can now watch a strain of bacteria become impervious to increasingly higher doses of an antibiotic—up to 1,000 times higher—in just 11 days.

Obviously, heaping larger and larger doses of drugs on already weak patients isn’t the solution. What we need isn’t stronger drugs, but smarter drugs.

Bacteria-virus warfare

Most of our current antibiotics work in one of few ways: interfering with the bacteria’s DNA repair system, stopping the bacteria’s ability to reproduce, or weakening the bacteria’s cell wall—something our cells don’t have—until it explodes.

“The downside of antibiotics is they are a sledgehammer that depletes and destroys the gut microbial community,” says Dr. Jan Peter van Pijkeren at the University of Madison-Wisconsin, who is working on CRISPR-based antibiotics. “You want to instead use a scalpel in order to specifically eradicate the microbe of interest.”

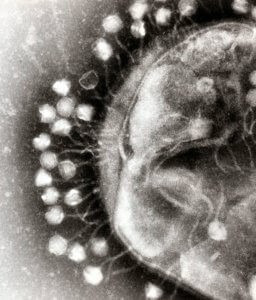

Phages are the white, bubble-like dots surrounding the larger round bacteria. Image Credit: Wikimedia

The new CRISPR pill eschews all traditional ideas, instead relying on the bacteria’s mortal enemy: a type of virus called bacteriophages (or, more endearingly, “phages”).

Like all viruses, phages can’t reproduce on their own. Instead, they constantly invade bacteria and inject viral genomes into the hosts, hoping to co-opt bacterial machinery to make armies of phage replicas.

This onslaught of foreign genetic material has spurred bacteria into developing a sophisticated defense system. When bacteria detect viral DNA, they store bits and pieces of it into their own genome to form a genetic sequence that we call CRISPR—a molecular “memory” of the phage, so to speak.

When the bacteria detect a matching viral DNA sequence, they activate CRISPR and, together with a pair of protein scissors called Cas-9, the system destroys the viral DNA. Voila, invasion blocked.

CRISPR antibiotics

Scientists have found that the CRISPR system doesn’t cut the bacteria’s own DNA under normal circumstances; when it does, the result is lethal.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

This spurred an ingenious idea: scientists could use phages to inject custom Trojan horses that trick the bacteria into cutting its own genes.

“The idea of CRISPR-based approaches is to enact sequence-specific antimicrobial activity, placing selective pressure against genes that are bad rather than conserved bacterial targets,” explains Dr. Timothy Lu at MIT.

Previously, Lu’s team successfully manufactured phages that carry DNA similar to antibiotic-resistant genes. Because the phage DNA was misdeemed a foreign invader, it spurred the bacteria’s CRISPR system into action, snipping away at its own genome and committing suicide.

Bacteria cells without the resistant gene didn’t sound their alarm bells, and in turn were spared and ended up dominating the population.

Similarly, van Pijkeren is working on a CRISPR pill that contains a phage harboring bits of genomic DNA of Clostridium difficile.

C. diff is an infection that is notoriously difficult to treat, causing long-term gastrointestinal distress in nearly half a million Americans in a single year, resulting in at least 15,000 deaths. The current best treatment—when antibiotics fail—is a fecal transplant from healthy donors, but the method is still considered experimental, and long-term effects are unclear (there is, of course, also the ick factor).

Because phages are readily chewed up in our stomach acid, van Pijkeren is working on packaging them up into Lactobacillus bacteria—a common probiotic often present in yogurt.

As an initial proof-of-concept step, the team has successfully engineered Lactobacillus bacteria to produce phages that target themselves. The next step, van Pijekeren explains, is to use these probiotics as “motherships” that travel the gut, dispensing phages along the way to infect any nearby C. diff, and tricking them into hacking up their own DNA.

“To…exploit these microbes to deliver therapeutics is very appealing because we know humans have been safely consuming them for thousands of years,” says van Pijkeren.

The long road

Promises aside, scientists already see several snags that might prevent the CRISPR pill from unleashing its full power.

Part of it is the delivery vehicle—the phage. Phages are rather particular about the types of bacteria they invade, and matching courier to target will require additional research.

Scientists also worry that if not all targeted bacteria are killed or if the process isn’t fast enough, some resilient members may evade the attack. Bacteria are also known to develop resistance to phage invasion—which means that if the treatment continues, selection pressure will push the population towards resistance.

But phages aren’t the only way to deliver CRISPR pills, and scientists are hopeful.

“The way I view it is not that we will be able to make an evolution-proof therapy, but that the genetic engineering tools will become more robust so that as evolution happens, we can rapidly develop countermeasures,” says Lu.

Banner Image Credit: Shutterstock

Dr. Shelly Xuelai Fan is a neuroscientist-turned-science-writer. She's fascinated with research about the brain, AI, longevity, biotech, and especially their intersection. As a digital nomad, she enjoys exploring new cultures, local foods, and the great outdoors.

Related Articles

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through February 21)

What the Rise of AI Scientists May Mean for Human Research

This ‘Machine Eye’ Could Give Robots Superhuman Reflexes

What we’re reading