Five-Year-Old Mini Brains Can Now Mimic a Kindergartener’s Neural Wiring. It’s Time to Talk Ethics.

Among pressing ethical concerns are whether brain organoids could one day feel pain or become conscious—and how would we know?

Image Credit

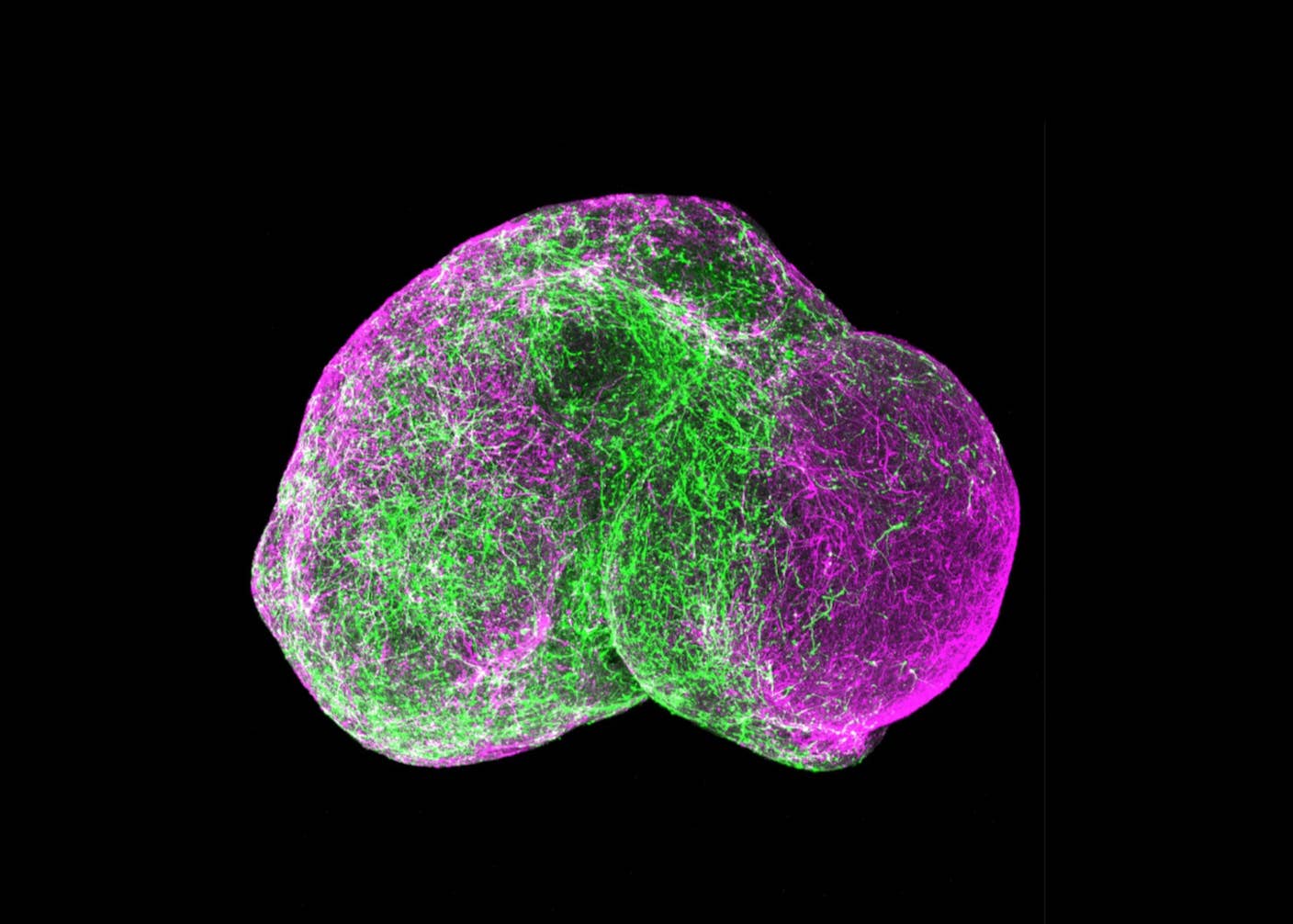

Brain organoids like this one mimic 3D structure of the brain. Pasca lab / Stanford via NIH

Share

When brain organoids were introduced roughly a decade ago, they were a scientific curiosity. The pea-sized blobs of brain tissue grown from stem cells mimicked parts of the human brain, giving researchers a 3D model to study, instead of the usual flat layer of neurons in a dish.

Scientists immediately realized they were special. Mini brains developed nearly the whole range of human brain cells, including neurons that sparked with electrical activity, making them an excellent way to observe and study the human brain—without the brain itself.

As the technology advanced and brain organoids matured, researchers coaxed them to grow structural layers with blood vessels roughly mimicking the cortex, the part of the brain that handles reasoning, working memory, and other high-level cognitive tasks. Parallel efforts derived organoids for other parts of the brain.

Mini brains can be made from a person’s skin cells and faithfully carry the genetic mutations that could cause neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism. The lab-grown blobs also provide a nearly infinite source of transplantable neural tissue, which in theory could help heal the brain after a stroke or other traumatic events. In early studies, organoids transplanted into rodent brains formed neural connections with resident brain cells.

More recently, assembloids have combined mini brains with other tissues, like muscles or blood vessels. These Frankenstein-ish assemblies capture how the brain controls bodily functions—and when those connections go awry.

As brain organoids have grown increasingly complex, ethical concerns about their use have grown too. After all, they’re made of neural tissue, which in our heads forms the basis of memory, emotions, sensations, and consciousness.

To be clear, there’s no evidence brain organoids can think or feel. They are absolutely not brains in a jar. But scientists can’t ignore the possibility they could eventually develop some sort of “sensation,” such as pain and, if they do, what that might mean for their development.

Aging Organoids

Harvard’s Paula Arlotta is among those who are concerned. An expert in the field, her team has developed ways to keep brain organoids alive for an astonishing seven years. Each nugget, smaller than a pea, is jam-packed with up to two million neurons and other human brain cells.

Studying these mini brains for years has delivered an unprecedented look into human brain development. Our brains take nearly two decades to mature, an exceptionally long period of time compared to other animals. As the team’s organoids aged, they slowly changed their wiring and gene expression, reports Arlotta and colleagues in a recent preprint.

In older organoids, progenitor cells—these are young cells that can form different types of brain cells—quickly decided what type of brain cell they would become. But in younger organoids, the same cells took time to make their decision. As the blobs grew over an astonishing five years, their neurons matured in shape, function, and connections, similar to those of a kindergartner.

These long-lasting organoids could reveal secrets of the developing brain. Some efforts are tracing the origins of different cell types and how they populate the brain. Others are generating organoids from people with autism or deadly inherited brain disorders to test treatments.

Excitement is at an all-time high. But while championing the research, Arlotta and other experts recently penned an article arguing for a global regulation committee to steer the nascent field.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Meeting of Minds

While scientists always keep ethics in the mind, they’re also motivated by scientific discovery and the search for new treatments. Plenty of promising research has also raised ethical concerns regarding sourcing or consent. Take the notorious CRISPR baby scandal in 2018. A Chinese scientist unlawfully and permanently altered a gene in embryos, and the children subsequently born with those DNA edits didn’t have a say in the matter.

Brain organoids present a different challenge. As they become more sophisticated and capture the brain’s cellular and structural makeup, could they begin to feel pain? Used in biocomputers, could they show signs of intelligence? Is it ethical to implant human mini brains into animals, where experiments show they integrate with host brains and blur the lines between man and beast? What about implanting lab-grown brain tissue into humans?

This November, experts (including Arlotta), ethicists, and patient advocates gathered at a conference co-organized by Stanford law professor Henry Greely, who specializes in bioethics. The meeting wasn’t designed to generate comprehensive guidelines regarding brain organoids. But ethics was a throughline during the entire conference as researchers presented recent successes in the field and pitched where it could go next.

In particular, Stanford’s Sergiu Pasca, a co-organizer of the meeting, attracted attention. Earlier this year, his team linked four organoids into a neural “pain pathway.” The model combined sensory neurons, spinal and cortex organoids, and parts of the brain that process pain.

The scientists dabbed the chemical behind chili’s tongue-scorching heat onto the sensory side of the assembloid. It produced waves of synchronized neural activity, suggesting the artificial tissue had detected the stimuli and transferred information.

That’s not to say it felt pain. Detecting pain is only part of the story. It takes a second neural pathway, which the assembloids lacked, to trigger the unpleasant feeling. But the experiment and others underscore the need for regulation. One idea pitched at the conference is to create a new global organization similar to the International Society for Stem Cell Research.

The commission would track advances in the field and provide oversight that balances scientific merit with patient needs. During the meeting, patients and family members expressed hope that mini brains could lead to new therapies, especially for those with rare genetic disorders or severe autism.

Pasca may soon deliver on that promise. His team is working to understand Timothy syndrome, a rare genetic disorder that leads to autism, epilepsy, and often fatal heart attacks. Last year they developed a gene-altering molecule that showed promise in brain organoids mimicking the disease. The treatment also worked in a rodent model, and the team is planning to submit a proposal for a clinical trial next year.

Drawing the line for brain organoid research will require global cooperation. “A continuing international process is needed to monitor and advise this rapidly progressing field,” wrote Arlotta, Pasca, and others. While there aren’t any universal agreements yet, dialogue on ethics, including discussion and engagement with the public, should guide the nascent field.

Dr. Shelly Xuelai Fan is a neuroscientist-turned-science-writer. She's fascinated with research about the brain, AI, longevity, biotech, and especially their intersection. As a digital nomad, she enjoys exploring new cultures, local foods, and the great outdoors.

Related Articles

Souped-Up CRISPR Gene Editor Replicates and Spreads Like a Virus

This Brain Pattern Could Signal the Moment Consciousness Slips Away

Vast ‘Blobs’ of Rock Have Stabilized Earth’s Magnetic Field for Hundreds of Millions of Years

What we’re reading