Somewhere along the road from sickness to health, the American medical system took a wrong turn—a big one.

The cost of care in our country is sky-high, yet our population health outcomes tend to be worse than those of other developed countries (many of which have universal health care). Major surgeries, treatments for long-term illnesses like cancer, and medical attention for catastrophic injuries are so expensive that people can lose their homes or be forced to declare bankruptcy. Even a routine visit to a general practitioner can cost hundreds of dollars. Yet Americans have some of the highest rates of heart disease, diabetes, and obesity in the world.

How did we get here?

In a talk at Singularity University’s Exponential Medicine summit this week in San Diego, Dr. Jordan Shlain shared his thoughts on that question, as well as a framework for moving American healthcare forward. The first step, he believes, is a new Hippocratic oath, one that’s been updated for our high-tech age.

From Care to Corporations

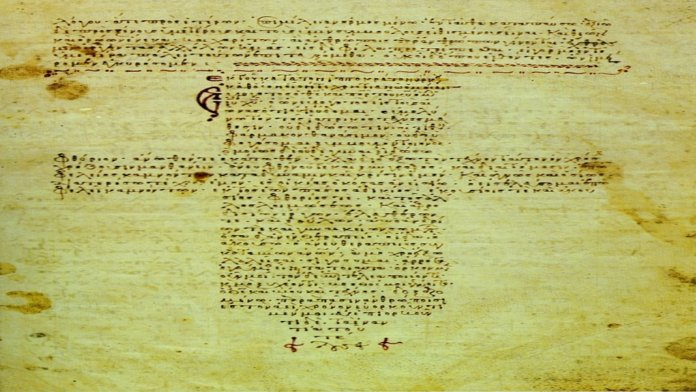

It was the fifth century BC when Hippocrates put forth the idea that physicians should try to help people and do no harm (a pretty intuitive concept, one would think), among other ethical standards. The Hippocratic oath was born, and over time it’s been modified to reflect shifts in medicine and society. But the field of medicine has changed even more than the oath has, and Shlain believes it’s time for another overhaul.

He pointed to the beginning of early modern medicine as pivotal to the field. As new technologies came along that had potential to treat people more effectively, everyone wanted access to those technologies, so someone had to start manufacturing them—and the incentive to do so was a profit.

“When X-rays and penicillin were invented, we could see things we’d never seen before and treat things we’d never been able to treat before,” Shlain said. “Someone had to make X-ray machines and someone had to form a pharmaceutical company.” But the convergence of medicine and business fed mounting costs, conflicts of interest, bureaucracy, and a focus on profits over patients.

Medical technology companies and pharmaceutical companies are now massive and complex, as are the medical and regulatory systems. “There’s a lot standing between physicians and patients,” Shlain said. “It leads us to reactive medicine, and there’s physician burnout.”

The root of this problem, he believes, is that a “corporate oath” has superseded the Hippocratic oath in healthcare. The corporate oath says to increase shareholder value, generate profits, and constantly grow margins. “But they don’t know the outcomes on the other side,” Shlain said. Exhibit A? The opioid crisis.

Since 1970, the costs of medications and medical devices have only gone up—and so have corporate revenues. went up, cost of devices went up. “But despite spending all this money and having all this expensive technology and medications, we’re not doing too well,” Shlain said, pointing to a graph that shows life expectancy in the US falling since 2014. “We need to differentiate between consumers and patients.”

Start Here

Shlain’s new oath consists of nine different statements.

1. I shall endeavor to understand what matters to the patient and actively engage them in shared decision making. I do not ‘own’ the patient, nor their data. I am a trusted custodian.

Shlain pointed out that rather than asking patients “What matters to you?” physicians ask, “What’s the matter with you?” But to get the right answer, it should be a combination, and not just between doctors and patients, but in every interaction in the healthcare system.

2. I shall focus on good patient care and experience to make my profits. If I can’t do well by doing good and prove it, I don’t belong in the field of the healing arts.

“We need to have some version of transparency for our outcomes,” Shlain said.

3. I shall be transparent and interoperable. I shall allow my outcomes to be peer-reviewed.

Silicon Valley has gotten better at embracing a culture of learning from failure and even encouraging failure as a path to eventual advancement, but the medical field hasn’t done the same—and perhaps rightfully so, since failure can mean a life lost. However, Shlain added, a byproduct of failure is almost always some sort of lesson.

4. I shall enable my patients the opportunity to opt in and opt out of all data sharing with non-essential medical providers at every instance.

Data privacy should be respected both as a path to trust and as a basic patient right.

5. I shall endeavor to change the language I use to make healthcare more understandable; less Latin, less paternal language; I shall cease using acronyms.

“I would rename type two diabetes ‘the over-consumption of processed food disease,’ because that’s what it is,” Shlain said. “You don’t ‘get’ it, you participate in its process. But you didn’t know it, because the language obfuscates that. So we really need to dig into language here, because language does tie to the metaphors we live by.”

6. I shall make all decisions as though the patient was in the room with me and I had to justify my decision to them.

7. I shall make technology, including artificial intelligence algorithms that assist clinicians in medical decision making, peer-reviewable.

“Everyone has proprietary technology and we’re supposed to use it despite not knowing how it works,” Shlain said. It’s in the interest of both practitioners and patients for this to change.

8. I believe that health is affected by social determinants. I shall incorporate them into my strategy.

“Someone’s zip code can tell you more about their health than their genetic code,” Shlain said. “We need to focus on community.”

9. I shall deputize everyone in my organization to surface any violations of this oath without penalty. I shall use open-source artificial intelligence as the transparency tool to monitor this oath.

Shlain pointed out that feedback loops in big corporations often aren’t productive, because people worry about losing their jobs. “We need to create some mechanism of a feedback loop to ensure that this happens,” he said.

This new oath isn’t just for clinicians, Shlain emphasized. It’s for everyone who touches the healthcare system in any way. That includes pharmaceutical companies, device manufacturers, medical suppliers, hospitals, and so on.

Given how fast new technologies are changing the healthcare landscape, we may need a totally new oath in ten years; what happens when robots are performing surgery, AI systems have taken over diagnosis, and gene editing can cure almost any congenital disease? We’ll need to continuously stay aware of how doctors’ roles are evolving, and update the ethical codes they practice by accordingly.

“What we need is a culture of care, at every level,” Shlain said. “In order to change our paradigm, we need to have a set of principles that get us there.”

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons