Will Virus Particles Meet Their End In These Tiny Death Traps?

Nanotechnology is gradually turning its hypothetical promise into real applications. Some see nanotech-based medicines as an entirely new set of tools in a doctor’s medical bag. Among commercial companies, Vecoy Nanomedicines is most bullish on the promise of nanotechnology to combat viruses.

Share

Whether or not the single biggest threat to humankind’s continued vitality on the planet is the virus, as Nobel Laureate Joshua Lederberg has said, there’s no question that viruses impose a hefty toll on human health worldwide. Though bacteria have been more or less conquered with antibiotics (though that's not as certain as it used to be), viruses have continued to thrive and mutate despite Western medicine’s best efforts to combat them.

But there’s a new kid on the medical block: Nanotechnology is gradually turning its hypothetical promise into real applications. Some see nanotech-based medicines as an entirely new set of tools in a doctor’s medical bag. Among commercial companies, Vecoy Nanomedicines is most bullish on the promise of nanotechnology to combat viruses.

The Israeli startup — whose founder, biologist Erez Livneh, fine-tuned the idea at Singularity University’s 2010 GSP program — is building a new class of medicines to fight viruses.

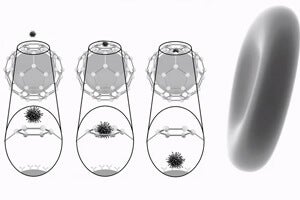

“The secret sauce here is not a specific material but a structure,” Livneh emphasized in his presentation at this year’s Solve for X event.

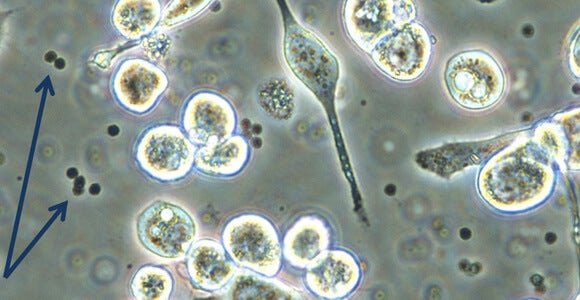

The structure is a nano-sized virus trap that would be administered in bulk, either with an injection or with an aerosol spray, to a patient who had been exposed to a virus. The polyhedron traps are large for nanomachines but still far smaller than a blood cell. Their outer layer dupes the immune system into recognizing it as friend, not foe, while pores in the surface are large enough to invite viruses in. After a virus enters, it meets with sharp pokers that physically destroy it.

“The Vecoy technology is the invention that solved a seeming paradox: How do you create a particle that’s attractive to viruses but that’s invisible to the immune system?” Livneh explained in a recent interview with Singularity Hub.

They claim that in a recent in vitro test, repeated rounds of the traps captured 97 percent of the viral copies that were floating around with human cells.

Vecoy is considering a number of different materials from which to build. But one seeming frontrunner is folded DNA, which has emerged as a viable raw material from which to build nanostructures. But some believe the biological material isn't a good building block because, even in its abstracted form, it would trigger an immune response.

“I feel that this approach could cause a dangerous, inflammatory innate immune response that could make the patient extremely ill,” said Stanford’s Annelise Barron. The immune response could potentially be averted, Barron said, if “the percentage of DNA in the ‘decoy’ construct could be adjusted to be minimal.”

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Supporters of so-called DNA origami, on the other hand, claim that the worst-case scenario will be that the body will biodegrade the DNA-based machines before they can perform their function.

“People ask, ‘How do you guarantee that this stuff will be ejected?’ but our challenge is guaranteeing it won’t be ejected too fast,” Livneh explained.

What would happen to the devices after they were administered to a patient and had done their work? In one scenario, the immune system would clear out the traps. In another, the traps would dissolve, releasing broken viral strands, which would hopefully help the immune system learn to target the virus more effectively on its own.

A wide range of potential uses for the mini virus traps can be envisioned. In addition to being administered to patients as medicine, they could be cycled through donated blood and other transplantable body fluids. They could also be used to purge water supplies of viruses such as polio. In that case, the traps would be made from magnetic material to be retrieved after use with a magnet.

It’s hard to argue with the need for a more effective ways of controlling viral illnesses.

“We need new ways of looking at viruses. The Spanish flu killed more than all the casualties of World War I by both sides. If that virus were to hit today, we’re not better off; we’re actually worse off with a denser population and international flights,” Livneh said. “This is exactly the kind of stuff that got me into science in the first place. It’s an opportunity to make a radical change for the better.”

Images: live cells and Vecoy nano-traps, viruses captured by nano-traps as seen under electron microscope, Vecoy technology diagram; all courtesy Vecoy Nanomedicines

Cameron received degrees in Comparative Literature from Princeton and Cornell universities. He has worked at Mother Jones, SFGate and IDG News Service and been published in California Lawyer and SF Weekly. He lives, predictably, in SF.

Related Articles

New Gene Drive Stops the Spread of Malaria—Without Killing Any Mosquitoes

These Robots Are the Size of Single Cells and Cost Just a Penny Apiece

Hugging Face Says AI Models With Reasoning Use 30x More Energy on Average

What we’re reading